This review is going to contain major spoilers of American Pie Presents: Beta House (2007) and 40 Days and 40 Nights (2002), as well as minor spoilers of Sex Education (2019-present). If you wanted to watch these, then here is your warning to stop reading and go and watch them.

Also, there are graphic discussions of sexual assault and transphobia in this post. If this is something that you are uncomfortable with or unable to cope with, I won't blame you for skipping it. Take care of yourself.

*

I truly hate the term 'guilty pleasure'. This isn't just because it creates shame around liking a thing but that it can often devalue that thing entirely, framing it as only worthy of attention because of some need to indulge in cringe. Like the only reason you would watch or read something would be to hate it. I think it's pretty common on the internet to only talk about the things you hate and when you do that, the conversation about that thing is very limited to its negative impact.

Also, sometimes I need the guilty pleasure. It fuels me.

The 'sex comedy' is what I would define as my guilty pleasure. I was even hesitant to write a meaningful analysis of this sub-genre because 1) it's not one that's seen to have any value, 2) many of them are very bad and very horny and 3) I don't want to be seen as a pervert. I think.

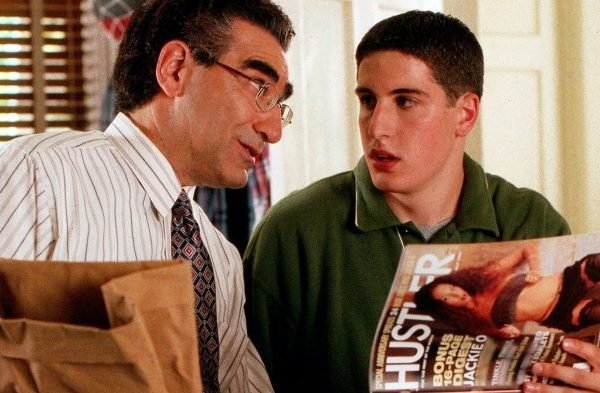

The reason I even wanted to write about them is specifically because of what they had to say about the way we view sex on-screen and who is choosing to portray it. Particularly in the early 2000s, there was a slew of films about teenage boys and young adult men coming (heh) into their manhood through their explorations of sex, often with, as Bill Osgerby puts it, 'brazenly over-the-top humour rooted in the salacious, the scatological and the squirmingly tasteless'.This could include anything from having sex with a pie to playing a game of 'greek roulette', where you take turns firing a gun filled with pellets of horse semen into your mouth, hoping you're not the one it lands on. (Both of these examples come from the American Pie series and its spin-offs, by the way). The audience these films seemed to want to attract were 14 year old boys who were looking to see boobies. Sharyn Pearce posits that they became 'a manual for self-formation, as a means whereby young men can progress relatively smoothly toward[s] adulthood', no matter the humiliations that come with this. In the first American Pie (1999), it is a running joke that Jim's father attempting to give him advice is embarrassing, mainly because he is far too late in his task of educating his son. The humour comes from how clinical and specific he is, asking straightforward questions like, 'do you know what a clitoris is?' to which Jim is horrified because of course he does! The audience is meant to squirm at the nightmare scenario that your parents want to talk about sex. Or worse. That they are having sex themselves and that they want to give you some tips.

|

| Source: Mandatory |

For me, however, it was, and continues to be, a fascinating look into the minds of American male screenwriters who seem to be obsessed with sex but unable to portray it in a sincere way, choosing to put their characters into embarrassing and even life-threatening scenarios, as a kind of self-harm and self-hatred of their former teenage selves. These films can be read as even more terrifying than the teenage girl brand of horror, e.g. Carrie (1976) or Jennifer's Body (2009); they feel like an exploration of the horrors of puberty and its relation to sex. It is unfortunate that very few of these seem to look at the sex comedy through a lens of queerness because it seems like it would be rife for this exploration. However, these films mostly just explore the pitfalls of heterosexuality, and how being a man involves obtaining a woman through sex.

When queerness does exist, it is relegated to a joke, as predatory (often in the case for men), or as a fetish (in the case for women). When trans people turn up, it's for a similar reason; to express the fear a cis man has about his sexuality or to trap a cis man into "actually having sex with a man". A major plot point of American Pie Presents: Beta House (2007) is that one of the characters, Cooze, is struggling to get his girlfriend to have sex with him, being relegated only to the dreaded handjob, and his friends theorise that she "might have a dick". This causes the character to have a nightmare where she does in fact have a penis and that wants him to have sex with her. Revealed at the end of the film, she isn't actually a trans woman and Cooze can finally breathe a sigh of relief. In case you missed the extremely hilarious joke here, it was that a trans woman might exist and may want to have sex with a cis man - her body not being cis was what the audience was meant to laugh at here. That was the gross-out scenario that these films tend to incorporate. The early 2000s really was not a good time for the LGBT community in cinema in general, but when your lifestyles and bodies become places of humour and fear for cis straight people, it is no wonder that the debates around these identities continue.

It stands to reason that if these films cannot seem to present queerness in any form without some kind of joke or panic surrounding it, that the women would also not be given complex and rich characters in relation to the pursuit of sex. As is expected, most of the female characters in these stories are objects, whether they are the main characters girlfriend or some random woman taking her clothes off. Their desire for sex and pleasure is rarely considered, or if it is, it still relegates them to the whims of a male character "getting off". And worse than this, the violations of consent in this genre seem to be a prominent feature.

I would hope that, post-MeToo, most audiences would react negatively to the nebulous boundaries of consent that is present in these films, something that is surprisingly not specific to gender. Much of these films involve a gag where (typically) a man will violate (typically) a woman's boundaries for the sake of being successful at obtaining sex. Women's autonomy is not often considered when say, a man films them stripping off or spies of them masturbating. Andi Zeisler points out that most of these stories hinge on the patriarchal idea that women needed to be 'tricked into sex' or 'punished for not giving it up'. Any methods may be used to obtain the sex, she argues, such as 'non-consensual surveillance in shower[s] and locker rooms, and drugged drinks', as these are the 'logical tools of boys and men who believ[e] sex to be their rightful reward'. In plain words:

'as a girl or woman, you exist only as a pesky delivery system for key body parts or a frustrating gatekeeper fated to be overthrown, by hook or by crook, by the dogged tenacity of male hormones.'

However, it is not just the case for women that boundaries are consent are violated. Much of the plot of 40 Days and 40 Nights (2002) surrounds Matt, a sex-obsessed man, trying to abstain from sex but who is tempted at every turn. At best, it is by the attractive woman he meets at the launderette and wishes to start a relationship with; at worst, it is through the attempts by people at his workplace (both men and women) to get him to break his vow, either by seducing him or spiking his drink with viagra. In order for the audience to get on board with the constant sexual harassment this man faces in the workplace, they must believe the gender essentialist idea that men always want sex and therefore, must want all advances from every woman all the time. So a woman sitting on a photocopier and flashing her underwear to a man in the workplace is meant to be viewed in a playful comedic way, where the man is having his secret desire expressed in front of him. The most heinous thing about this film is its ending, a horribly graphic scene where the protagonist, after hand-cuffing himself to the bed to prevent any more temptations, is raped by his ex-girlfriend in his sleep. As Mika Doyle states, the worst thing about this is that it's not framed as sexual violence; 'instead, it’s portrayed as Matt “cheating”'. Doyle very rightly points out that Matt winds up apologising to the girl he was seeing, 'meaning he has to apologize for being raped'; when the rape of men is played for laughs in this way, it means that 'a violent act [becomes] unrecognizable as rape to the audience'. The tragedy in this scene is not the assault, but rather that he broke a promise to his love interest by allowing this to happen to him.

|

| Source: Tontiag |

The insensitivity in these films, and by that I mean the reliance of punching down at marginalised groups for the sake of humour, is a feature of these films, not a bug. They often explore the horror adolescent straight boys have about their own sexuality in relation to their masculinity, and in many ways, these characters feel disempowered in how they view themselves. Unable to express these insecurities without being viewed as effeminate or being emasculated by their peers, the characters, as well as the writers, choose to exert what power they do have - the power to laugh at those they themselves view as odd: the racial other, queerness, disability, and especially women. The edgy gross-out humour tends to express a desire to laugh at something outside of yourself because you feel without power or influence. It is not Asian people making the jokes about their race; it isn't smaller people making the "midget" jokes; it isn't trans people who are obsessed making jokes about their own bodies. It is always the white cis men portraying the spectacle of these people. An article in the Metro explains that in relation to jokes about trans people, often the joke is that people are trans in the first place and that when this is done for laughs, 'there is often little concern shown for the effect it might have on real people', and I think this can be applied to how marginalised groups in general are portrayed in all comedy, not just the sex comedy.

These films are often less about pleasure and more about the masochism of adolescence. These characters are created to be tortured, so that the filmmakers can assuage the insecurities they feel about their own bodies, their own sexual performance and how they are viewed by other men. As Scott Tobias argues, these films are essential 'humiliating rites of passage' for the characters and 'a perverse form of escapism' for the audience.

Now, I wouldn't be discussing this genre at all if I didn't think it was important. Being able to laugh at yourself can and should be normal. What the issue seems to be here is that in men writing stories where they flagellate themselves for not being sex gods, they seem to drag everyone else under the bus, the end being the men are finally able to complete their quests of sexual domination and everyone else who was also along for the ride gets sidelined for a quick joke or a meaningless object. Some of these film posit that it's love that men should be pursuing, swapping out one absolute for another. Love gets sex, sex gets love. Without the nuances there, often the pleasure of these pursuits feels stale and, as a result the comedy does as well.

|

| Source: Variety |

What I've found in more recent examples is that, whilst we can laugh at the shortcomings that come with not knowing what you are doing sexually, the butt of the joke almost never seems to be at the expense of a marginalised group, and that gross-out humour doesn't necessarily need to be abandoned either. In the opening of the second season of Sex Education (2019-present), we see Otis, a character who had previously been adverse to masturbation due to trauma, masturbating in what seems like a constant cycle. The joke becomes that he is turned on by absolutely everything, even cheese. The sequence ends with him masturbating in the car and and as his mother walks passed, he ejaculates onto the window. This is scene that would absolutely fit in with one of the American Pie films. However, the context is entirely different. As the title suggests, the show prioritises sex education, including that of queer and other marginalised identities, but more importantly than that, Cameron Glover states there is a 'centralising of pleasure' and the sex is 'more than just performance and orgasms; it’s a layered human experience'.

What these additions to the genre provide is access to unheard voices regarding sex, as well as a meaningful critique to some of the bizarre tropes regarding how women feel about sex, and how queerness plays a part in the coming of age sex story. They give the audiences an opportunity to cringe at our teenage selves with the understanding that young people are not meant to know everything and not punishing them, through masculinised hazing rituals and violations of consent, for not being a sexually literate adult. We can in fact laugh at sex without making those different than us the butt of the joke.

The jokes in the film Yes, God, Yes (2020) are not that the characters are inexperienced but rather that the way sex is talked about is often hypocritical, especially in religious circles. The protagonist being slut shamed is not the joke, it's the problem. Many of the jokes come from her ignorance, such as her rushing to the internet to try to find out what a rimjob is. The blend of naivete and experience becomes what the protagonist must reckon with. The chaste counsellor saying that even though he wants to kiss the protagonist, that she shouldn't pursue him because he gets 'turned on like a microwave' is a funny situation because of the framing, because of the absurdity. Very little of its humour is based on the characters being shamed simply for wanting sex, but rather the absurd idea that they shouldn't be pursuing it at all.

|

| Source: Nebraska Today |

Similarly, the film The To Do List (2013) captures what early 2000s sex comedies were trying to do from a young woman's point of view, with the main character, Brandy, creating a list of acts she wants to do before she goes to college. Zeisler argues that this film 'normalizes the idea that teen girls not only have the same desires as their male counterparts, but use the same language to discuss them', putting Brandy in similar situations where she can be humiliated and also validated for her desires. This film feels less masochistic, seeking to attach pleasure to Brandy's pursuit and make fun of those who seek to shame her for moving forward with it. In centralising a teenage girl in this story, it argues that many of the early comedies were wrong: women are horny and would like sex as well, even if that sex doesn't come because of coercion or at the promise of a relationship.

To an extent, the type of 'sex comedy' I liked to watch when I was teenager is dead. I read many articles stating that American Pie (1999) couldn't be made today, these being written in reaction to new people coming in contact with the films and critiquing them heavily for some of the same things I have in this post. And I think it's probably a good thing that films like this couldn't be made today. Whilst I have a soft spot for them and will probably return to them, I actually look forward to the way the sex comedy can evolve with the inclusion of new voices. In their original form, they only seemed to offer a surface-level critique of the way men often view sex, which was unhelpful and harmful. In their new form, they could help us view something not talked about at all as something that's really not that serious.

*

Thank you for reading this post! If you enjoyed it, please consider donating to my Ko-fi. It's a one time donation of £1 and it would really help me out x

Sources:

Andi Zeisler, '“The To-Do List” is the '80s Sex Comedy We Wish Had Existed in the Actual '80s', bitchmedia <https://www.bitchmedia.org/post/the-to-do-list-is-the-80s-sex-comedy-we-wish-had-existed-in-the-actual-80s> [accessed 24/02/2021]

Bill Osgerby, American Pie: The Anatomy of Vulgar Teen Comedy (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020).

Cameron Glover, 'The Final Frontier With “Sex Education,” Netflix Expands the Pleasure Discourse', bitchmedia <https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/netflix-sex-education-season-two-review> [accessed 24/02/2021]

Mika Doyle, 'Male Rape is No Joke—But Pop Culture Often Treats It That Way', bitchmedia <https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/male-rape-no-joke%E2%80%94-pop-culture-often-treats-it-way> [accessed 24/02/2021]

Scott Tobias, 'American Pie at 20: why the raucous comedy could never be made today', The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/jul/09/american-pie-20th-anniversary-jason-biggs> [accessed 24/02/2021]

Sharyn Pearce, '"As Wholesome As...": American Pie As a New Millenium Sex Manual' in Youth Cultures: Texts, Images and Identities, ed. by Kerry Mallan and Sharyn Pearce (Connecticut: Praeger, 2003), pp. 69-80.

Ugla Stefanía Kristjönudóttir Jónsdóttir, 'Comedy about trans people is fine – just don’t make us the butt of the joke', Metro <https://metro.co.uk/2020/12/02/comedy-about-trans-people-is-fine-just-dont-make-us-the-butt-of-the-joke-13682252/> [accessed 24/02/2021]